How scholars assess academic paper recommendations

Project background

Academic recommender systems have become a central part of how scholars discover new work. Yet both public and internal narratives around these systems tend to focus on model performance (e.g., click-through rates, embedding similarity) rather than on how people actually reason about recommendations in context. In context, scholars frequently described recommendations as “interesting but not what I need right now,” “too old to be useful,” or “from venues I don’t trust.” Papers could be technically “on topic,” but still feel irrelevant, not credible, or misaligned with current research needs. To understand this mismatch, we conducted a qualitative study focused on scholars’ real-time evaluation of recommended papers.

Research questions

What criteria do scholars use to evaluate the value of a recommended paper?

How do scholars decide whether to read or ignore a specific recommendation?

Where do these human evaluation processes diverge from the assumptions of the existing recommendation model?

Methods

We recruited 11 scholars across multiple disciplines (including social sciences, humanities, and STEM), at different career stages (faculty, postdocs, and research professionals).

Findings

1. A Multi-Stage Evaluation Pipeline

Across participants, we observed a consistent and rapid sequence for evaluating recommended papers. Scholars first assessed topical fit, followed by recency, then credibility signals (author identity, affiliation, and venue). Only recommendations that passed these initial filters prompted a deeper review of the abstract, where participants looked for contribution and novelty.

Figure 1. Cognitive evaluation pipeline for recommended papers.

2. Metadata Fields as Distinct Cognitive Signals

Table 1. Attribute framework mapping metadata fields to perceived value. This table summarizes how each metadata field supports specific assessments (e.g., relevance, recency, credibility, novelty) and the questions scholars asked when making these judgments.

Participants treated each metadata field as a distinct evaluative signal. Titles were used to assess topical relevance, while publication dates served as a fast filter for recency. Author identity and institutional affiliation functioned as credibility cues, as did journal or conference venue, which often determined whether a paper was considered trustworthy.

Only after a recommendation passed these early filters did participants read the abstract—primarily to infer novelty and contribution. Importantly, novelty and contribution did not appear as direct metadata fields that’s available on initial scan.

3. Social Proof as an Independent Cue of Importance

Beyond metadata fields, scholars also relied on a separate class of signals rooted in their social networks. Social signals—such as seeing that a respected scholar had uploaded or bookmarked a paper—had strong influence on perceived importance:

“If she’s reading this, I at least want to know why.”

These social cues drew attention to a specific recommendation, and sometimes elevating recommendations into must-read items, even when other signals (e.g., venue, topic) were ambiguous.

4. Current interests, not historical behavior, drive relevance

Participants consistently framed relevance in terms of current projects, not entire careers or historical interests. Papers connected to prior research trajectories were frequently rejected:

“I worked on this topic years ago; I don’t need more of it now.”

This conflicts with the recommendation model’s heavy reliance on long-term behavior logs and topic history. The system treated all past behavior as a stable signal of interest, whereas scholars treated relevance as highly time- and project-dependent.

5. Scholars Prefer Over-Inclusion to Missing Critical Work

Participants expressed a clear asymmetry in how they viewed errors:

False positives (irrelevant recommendations) were seen as mildly annoying but easy to ignore.

False negatives (missing relevant papers) were perceived as high-cost, since they risked overlooking important work.

As one participant put it:

“I’d rather scroll past a bunch of things that don’t matter than have the system hide something I really need.”

This asymmetry suggests that scholars tolerate some noise in their feeds as long as recall for high-value items is high.

6. Human–Algorithm Mismatches

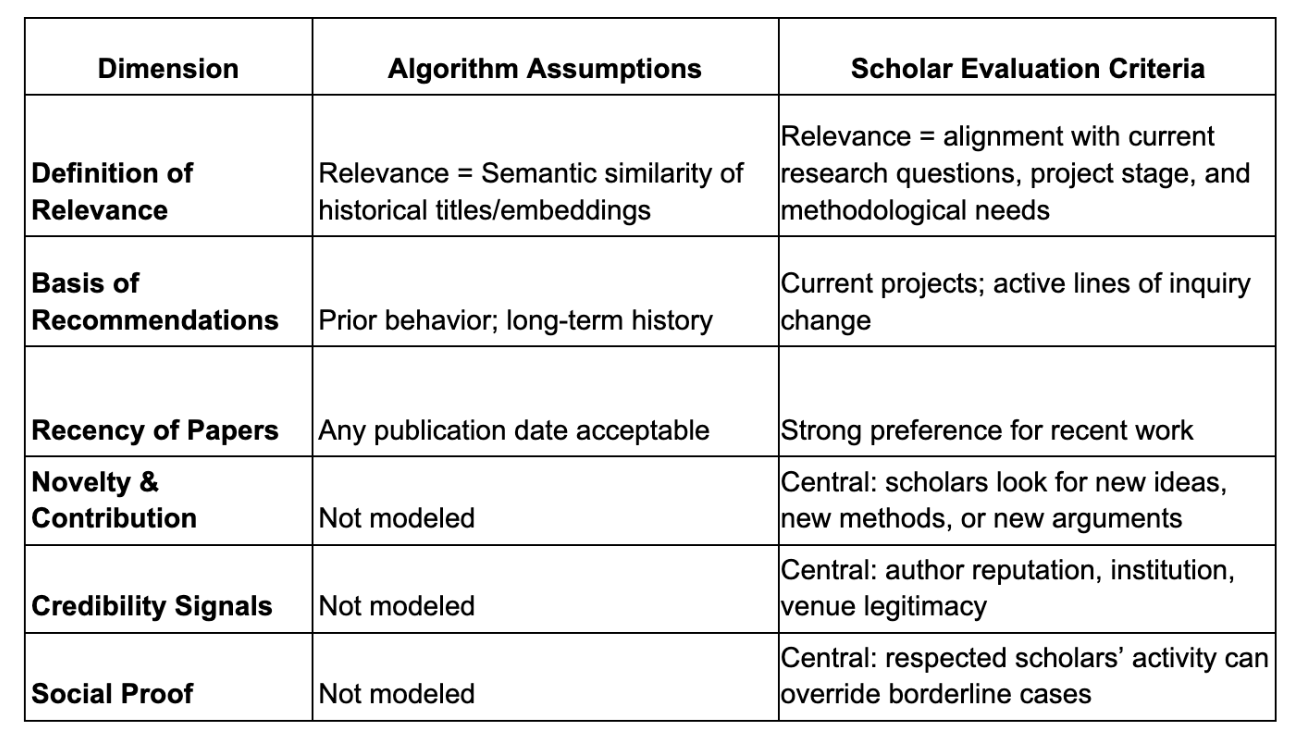

Table 2. Human–Algorithm Mismatches in Assessing Paper Recommendations

Comparing scholars’ real-time evaluation practices with the assumptions embedded in the existing recommendation model reveals several systematic divergences. The model implicitly defined relevance as semantic similarity to historical titles and past interests. Scholars did not. For them, relevance was contextual and multidimensional—requiring alignment with current research questions, project stage, recency requirements, credibility cues, contribution type, and novelty. As a result, many semantically “correct” recommendations felt irrelevant because they did not match what the scholar was working on right now.

These mismatches highlight a deeper conceptual gap: algorithmic definitions of relevance are narrow and static, while scholars’ definitions are broad, contextual, and dynamic. Understanding this gap is essential for designing recommender systems that match real scholarly decision-making and correctly prioritize users’ limited attention.

Implications

Recommendation model

Findings suggest several adjustments to model design:

Prioritize current project needs rather than treating all historical behavior as equally relevant.

Strengthen recency weighting to match scholars’ expectations that outdated work is often less useful.

Incorporate credibility signals, including author prominence, affiliation, and venue quality.

Approximate novelty, for example by detecting new methods or problem framings.

Interface design

Interfaces should be structured to match the cognitive pipeline:

Surface information in the order scholars actually evaluate it.

Make credibility cues (affiliation, venue) more visible and scannable.

Create novelty signals to use a scannable metadata.

Organizational impact

It also opened up company conversations that extended beyond the algorithm and interface such as:

Explore incorporating paper corpus that weighs towards more recent papers.

Redesign onboarding flow to collect information about their current research interests.

Increase focus on increasing social activity and sharing of papers

Limitations

This study has several limitations:

Participants were recruited from a single platform (Academia.edu) and are not representative of all scholars.

The sample size (n = 11) is appropriate for process discovery but not for estimating population-level prevalence.

We did not include behavioral logs; analysis relied on self-report and observed evaluation in interviews.

Disciplinary differences in evaluation criteria merit deeper, domain-specific investigation.

Think-aloud protocols may increase cognitive load and encourage more deliberate, rationalized explanations than scholars typically use in real-time scanning.

Future work could combine this cognitive framework with large-scale behavioral data to test how different recommendation strategies affect long-term engagement.

Conclusion

Scholars evaluate paper recommendations using a rapid, structured, multi-attribute process that differs substantially from typical recommendation model assumptions. Rather than treating semantic similarity and historical interests as sufficient, recommender systems for scholarly work must account for current project fit, recency, credibility, contribution, and novelty, as well as social signals.

By aligning model design and interface presentation with these human evaluation processes, platforms like Academia.edu can better support meaningful discovery and more accurately reflect how scholars decide what is worth their limited attention.