Americans living paycheck-to-paycheck

At-a-glance summary

What we studied: How Americans experience and navigate living paycheck-to-paycheck, using mixed-methods research inside a large U.S. credit platform.

What we found:

Financial instability is driven by shocks and structural constraints, not poor budgeting.

Once destabilized, people enter a self-reinforcing debt cycle that is difficult to exit without systemic support.

Why this mattered: Paycheck-to-paycheck living is a dynamic, long-term condition, shaped by past events, constrained cash-flow, and cognitive load under scarcity—not a series of bad choices.

Impact: These findings reframed company strategy, shifting focus toward cash-flow stability, collections clarity, and structural support—including a bank acquisition to better serve paycheck-to-paycheck users.

Project background

Despite widespread media attention, the lived experience of financial instability remains poorly understood. Roughly 41% of Americans have less than $2,000 in savings, a threshold below one month of necessities. Behavioral science suggests that scarcity narrows cognitive bandwidth, leading to short-term, survival-oriented decision-making. This study investigates how financially vulnerable consumers experience, describe, and navigate the paycheck-to-paycheck cycle using a multi-method research program within a large U.S. credit platform.

Research questions

How do financially vulnerable individuals define “living paycheck-to-paycheck”?

How does financial instability begin and evolve over time?

What structural and behavioral mechanisms reinforce instability?

Methods & participants

Participants were recruited from a large financial platform, Credit Sesame.

We used a mixed-methods triangulation framework combining:

Literature review

On-site intercept surveys (n ≈ 1100)

Behavioral analytics from millions of credit files

Semi-structured interviews (n = 12)

Systems modeling (cycle, timeline, opportunity tree)

Findings

Finding 1. Defining “Paycheck-to-Paycheck”

Participants converged on a functional definition:

“If I miss one paycheck, I cannot cover next month’s necessities.”

Quantitatively, this typically meant:

Less than $1,000 in leftover income after essentials

Less than $2,000 in liquid savings

High fixed expenses (rent, childcare, transportation, medical payments)

This user-derived definition provides an empirical operationalization of “paycheck-to-paycheck” grounded in lived experience rather than moral narratives.

Finding 2. Pathways Into Instability: The Shock-Initiated Debt Cycle

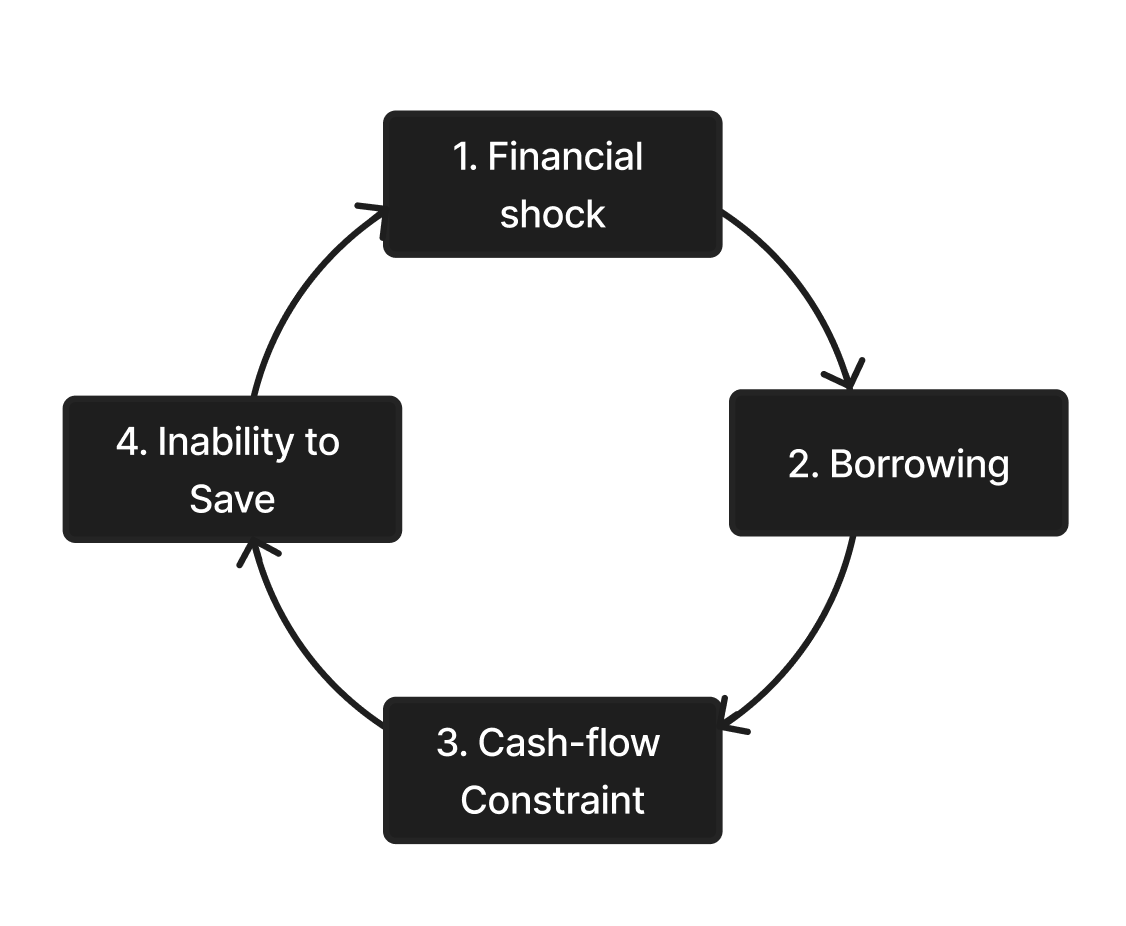

Across interviews, current financial precarity was consistently mapped back to one or more destabilizing financial shocks (e.g., medical event, job loss), which initiates borrowing, which reduces future cash-flow via payments, interests, and penalties, preventing savings and increasing vulnerability to subsequent shocks. This model explains the persistence of financial instability as a structurally reinforced feedback loop rather than a sequence of isolated events.

Figure 1. Debt Cycle Model.

Finding 3. A Temporal Model of Financial Instability

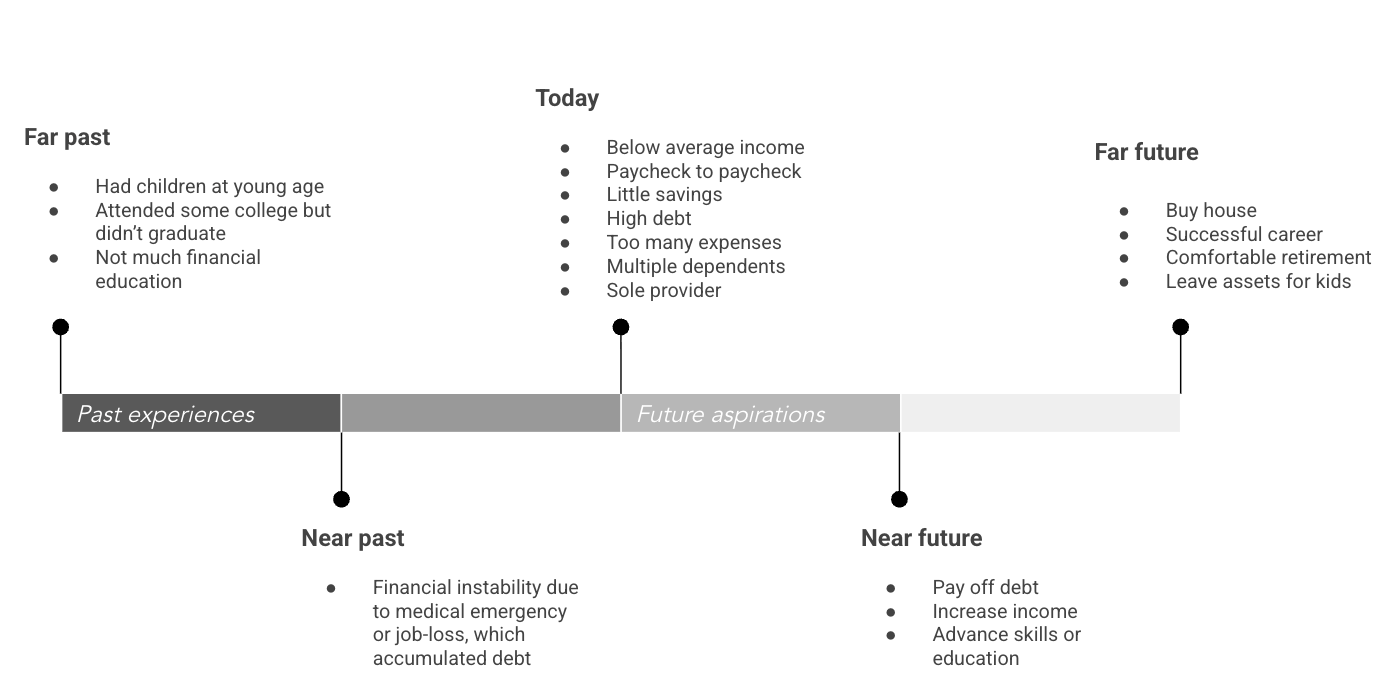

Participants’ narratives could be synthesized into a common temporal pattern: early constraints, a destabilizing shock, sustained present-day precarity, and future-oriented hopes. The temporal model highlights that financial instability is not a static state but a dynamic trajectory shaped by prior events and constrained futures.

Figure 2. Temporal Instability Timeline

Finding 4. Root Causes: The Opportunity Tree

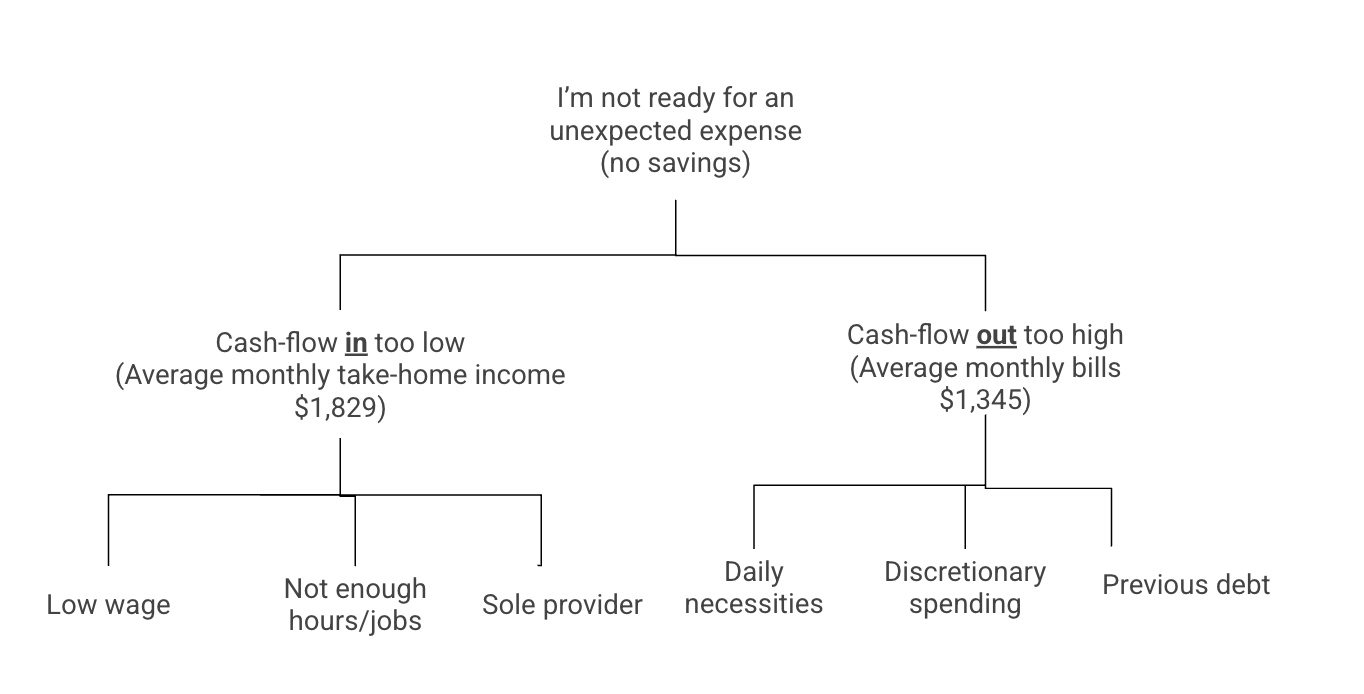

Synthesis across data led to a root-cause framing centered on a top-level problem:

“I am not prepared for an unexpected expense.”

The opportunity tree is a functional decomposition of why users are unprepared for unexpected expenses, separating “cash-flow in too low” from “cash-flow out too high,” and identifying sub-causes and possible intervention points. It highlights structural drivers and identifies where interventions—product, policy, or educational—are most likely to have leverage.

Figure 3. Root-Cause Opportunity Tree.

Finding 5. Deeper Dive: The Burden of Collections Debt

Credit analytics revealed:

63% of financially vulnerable users had at least one open collection

The mean collection balance was approximately $963

Collections were present across the full range of credit scores

Survey analysis found:

25% of users with collections were unaware they had them

Of those who were aware, 60% were not making payments

Follow-up interviews indicated that non-payment was driven by:

Confusion about which collections were valid

Fear of engaging with collectors

Shame and avoidance

Perception that payments would not materially improve their situation

These findings suggest that collections are both a financial burden and a cognitive/emotional burden, reinforcing the broader scarcity trap.

Implications & impact

Design Implications

For financial products and services, the findings highlight the need to:

Provide clear, actionable information around collections (what is owed, to whom, and what options exist).

Reduce cognitive load by simplifying decision paths and automating small, incremental steps (e.g., micro-savings, payment plans).

Align bill due dates with pay cycles where possible to reduce predictable shortfalls.

Treat financial vulnerability as an ongoing state shaped by past events, not a single moment of “bad choices.”

Policy Implications

At a policy level, the models suggest that:

Mitigating income volatility and medical debt could substantially reduce the number of households entering the debt cycle.

Strengthening safety nets around shocks (e.g., paid leave, emergency aid) may prevent the initial descent into instability.

Reforming collections processes and penalties may reduce both financial and cognitive burdens on already vulnerable households.

Organizational Impact

This research shifted internal understanding of financial instability from individual failure to structural vulnerability. Evidence showed that many users lived paycheck-to-paycheck due to shock-driven debt and systemic constraints, not poor budgeting. As a result, the company reframed paycheck-to-paycheck users as a core audience and redirected strategy toward addressing root causes such as cash-flow volatility, collections confusion, and financial scarcity. These insights informed a broader product and identity shift, including the acquisition of a bank and the development of tools for emergency savings, cash-flow smoothing, and debt resolution.

Conclusion

Living paycheck-to-paycheck is often framed as a personal failing, yet the evidence from this study points to a systemic, shock-driven, and structurally reinforced condition. Through mixed-methods triangulation and conceptual modeling, we show that financial instability is the logical consequence of past shocks, constrained cash-flow, high fixed costs, and cognitive load under scarcity.